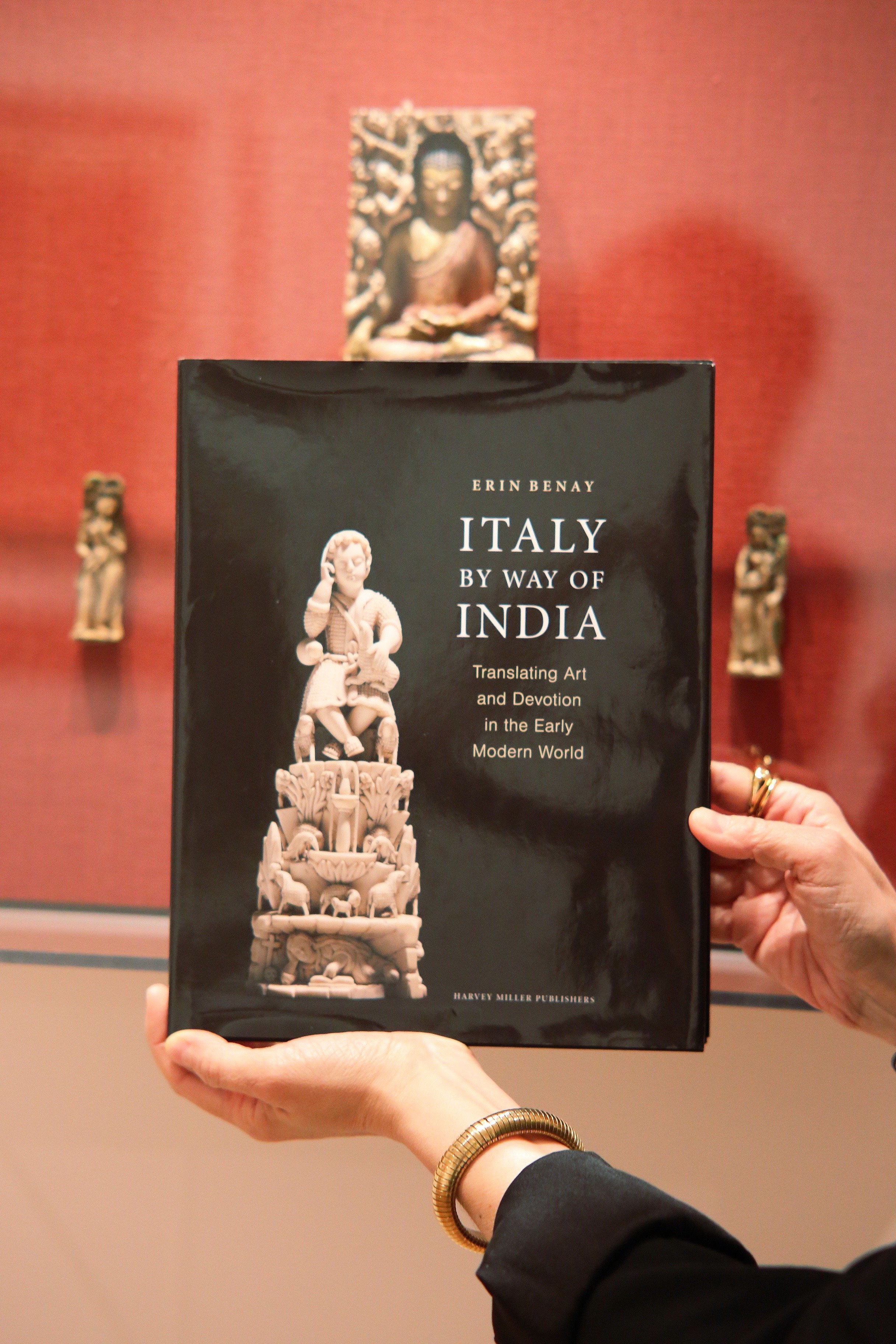

Italy by Way of India

The return of a saint’s body to its rightful resting place was an event of civic and spiritual significance retold in Medieval sources and substantiated by artistic commissions. Legends of Saint Thomas Apostle, for instance, claimed that the martyred saint had been miraculously transported from India to Italy during the thirteenth century.

However, Saint Thomas’s purported resting place in Ortona, Italy did not become a major stopping point on pilgrimage or exploration routes, nor did this event punctuate frescoed life cycles or become a subject for Renaissance altarpieces as one would expect.

Instead, the site of the apostle’s burial in Chennai, India has flourished as a terminus of religious pilgrimage, where a multifaceted visual tradition emerged, and where a vibrant local cult of ‘Thomas Christians’ remains to this day. An unlikely destination on the edge of the ‘known’ world thus became a surprising source of early modern Christian piety.

By studying the art and texts associated with this little-known cult, this book disrupts assumptions about how knowledge of Asia took shape during the Renaissance and challenges art historical paradigms in which art was crafted by locals merely to be exported, collected, and consumed by curious European patrons.

In so doing, Italy by Way of India proposes that we redefine the parameters of early modern visual culture to account for the ways that global mobility and the circulation of objects profoundly influence how cultures see and know each other as well as themselves.

International Praise for Italy by Way of India: Translating Art and Devotion in the Early Modern World

“Italy by Way of India is a groundbreaking study. It promises to change not only how we approach artistic exchange between colonial India and Europeans but also how we reconceptualize the ways that artworks move through time and space to produce global knowledge.”

— Dr. Erin J. Campbell, Renaissance and Reformation

“[Italy by Way of India] is an eyeopener. The author seems to have turned the kaleidoscope–which for a very long time had produced a certain pattern–just a little further, so that all the colorful plates and set pieces could produce a completely new picture.The book accomplishes a great deal: Erin Benay introduces for the first time the visual and material culture of the St. Thomas Christians into our thinking of an entangled early modern art history. In the process, she analyzes previously rarely if ever looked-at wall paintings, altar frames, wooden church ceilings, granite monumental crosses, goldsmith liturgical objects, and painted alms boxes.”

— Dr. Urte Krass, 21: Inquiries into Art, History, and the Visual – Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte und visuellen Kultur

“Let us celebrate this fine study, which must surely constitute a template as well as a clarion call for more such studies of the multifarious and reciprocal ways in which Christianity was translated visually between the Old World and the Indies (East and West).”

— Dr. Simon Ditchfield, Journal of Early Modern History

“[Benay’s] work, which draws together many types of evidence, material and textual, is a methodological tour-de-force that avoids the problematic dichotomy between center and periphery by showing that Thomas Christianity predated the arrival of missionaries and merchants from Italy and Portugal by many centuries. Benay also effectively debunks the historical paradigm which assumes that local artisans produced ivory and other devotional objects exclusively for the global market in luxury goods and were uninvested in their Christian content. This superbly conceived examination of artistic exchange.”

— Dr. Claire Farago, Brepols|Harvey Miller Publishers

“ Et elle réalise ce qu’elle prêche : le nationalisme hindou du gouvernement indien actuel, tout comme l’essentialisation du sous-continent par l’historiogra- phie européenne et eurocentrique (historiographie de l’art y comprise, que Benay lit avec un esprit critique aiguisé), sont efficacement relati- visés par le récit complexe, pluriel, multidirectionnel, décentré, et sou- vent merveilleusement fluide, que propose Italy by Way of India.”

— Dr. Itay Sapir, RACAR, Journal of the Universities Art Association of Canada

Reviews

Note About Methodology

This book makes extensive use of archival sources, namely housed in Italian and Portuguese archives.

Although I consulted numerous archives in India, including the archives in the Madurai Province of the Jesuits at Sacred Heart College, Shembaganur, Kodaikanal, Dindigul District, Tamil Nadu; the archives of the Museum of Christian Art, Santa Monica Convent, Goa; the archives of the Indo-Christian Museum in Cochin, Kerala; the archives of the National Museum, Delhi; the Kerala State Archives; Tamil Nadu State Archives, Egmore, Chennai; the manuscript collection of the Madras University Library, Chennai; the Roja Muthiah Research Library, CPT Campus, Tasamani, Chennai; the Malabar Digital Archive; the church archives of Synod Church, Udayamperoor, Thrippunithura, Ernakulam, Kerala; and the archives of the Saint Thomas Christian Museum, Kakkanad, I was largely unable to find textual archival sources about Christian art in this milieu and so they are not footnoted in the book.

I also consulted the Epigraphia Indica extensively, searching for the inscriptions that are often central to the interpretation of Indian art. I found none for the objects I discuss in this book. As numerous recent discussions of ‘the Archive’ writ large have demonstrated, archives are not neutral and therefore it is not entirely surprising that I was unable to find records about lower-caste, indigenous artists or their ‘workshops.’[i]

I hope that future scholars will be able to build on and expand my work and will, ultimately, locate this type of conventional, textual evidence. My argument, however, hinges on the close visual analysis of works of art as archives of indigenous activity.

In order to make those arguments, I draw on the work of numerous scholars of international origins, including many Indian art historians and historians (including Anand Amaladass, Jitendra Nath Banerjea, V.P. Dwivedi, George Menachery, Sharma Preeti, A. Ramachandran, and Pushkar Sohoni, all of whom are cited in my book).

Although I met with numerous Church Fathers, whose work about Thomas Christianity is informed by their own spiritual practices, these conversations and their publications (which are widely available and sometimes over-cited) were at times too biased to be included in the book. I also met with and benefitted enormously from the expertise of Indian scholars, including Natasha Fernandes, Susan Deborah Selvaraj,V. Sathish, Kanaklata Singh, George Menachery, and Dr. Murugesan. Finally, discussions with US-based South Asianists were also crucial to my thinking, including conversations with Drs. Richard Asher, Sonya Rhie Mace, Arathi Menon, Romita Ray, and Yael Rice.

All of these informal correspondences are not cited in my book but were of course, formative.

No book can do everything nor cite everyone; it is my hope that this study offers an important foray into the complex lives of objects that move and whose identity is anything but fixed.

[i] On the impacts of colonialism on the ‘archive’ as a broader concept, see for example: the essays in Sources and Methods in Histories of Colonialism: Approaching the Imperial Archive (edited by Kirsty Reed and Fiona Paisley (Routledge, 2017); Saloni Mathur, India by Design: Colonial History and Cultural Display (University of California Press, 2007); Barabara E. Mundy and Aaron M. Hyman, “Out of the Shadow of Vasari: Towards a New Model of the ‘Artist’ in Colonial Latin America,” Colonial Latin American Review 23 (2015): 283-317. This issue extends beyond the parameters of colonialism per se; see for example Julie L. McGee, “The Artist and the Archive: African American Art,” (in The Routledge Companion to African American Art History, edited by Eddie Chambers (New York and London: 2020), 327-338.

Citation: Benay, Erin. Italy by Way of India: Translating Art and Devotion in the Early Modern World. Turnhout: Brepols|Harvey Miller, 2021. To order click here.